Leaky Gut Syndrome from a Clinical Perspective: Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Evidence-Based Treatment Approaches

Introduction to Leaky Gut Syndrome

Leaky gut syndrome, characterized by impaired intestinal permeability, has gained attention in both scientific literature and clinical practice. This condition is associated with various gastrointestinal and systemic diseases, although its clinical significance remains a topic of debate. The present review examines the mechanisms underlying leaky gut, its diagnostic measures, potential etiological factors, and treatment strategies, with a focus on evidence from human studies. The aim is to provide clinicians with a comprehensive understanding of leaky gut, its clinical implications, and current approaches to management, while highlighting the work of Dr. Steven Gundry in supporting gut health through dietary interventions.

What is Leaky Gut Syndrome?

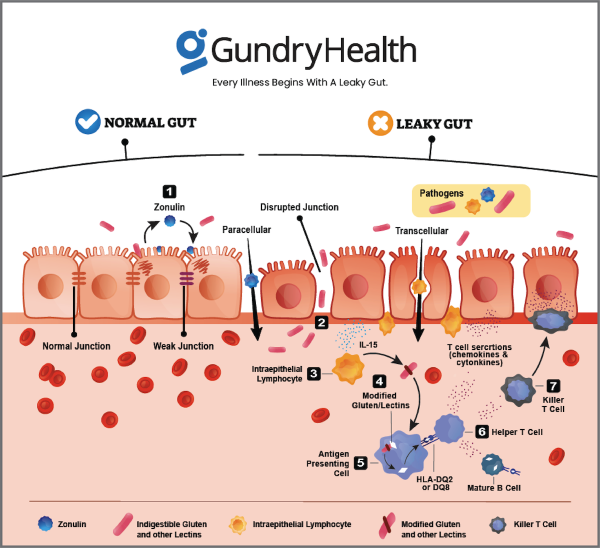

Leaky gut syndrome refers to an increase in intestinal permeability, which results in the unintended passage of harmful substances, including bacteria, toxins, and undigested food particles, into the bloodstream. This phenomenon is typically associated with the disruption of the epithelial cell barrier in the small intestine. The integrity of this barrier is maintained by tight junctions between epithelial cells, which control the passage of materials between cells. When these junctions are compromised, intestinal permeability increases, potentially leading to systemic inflammation and immune activation. While leaky gut is most often studied in the context of gastrointestinal diseases, increasing evidence suggests its relevance to a broad spectrum of disorders, ranging from autoimmune conditions to mental health disorders.

Leaky gut syndrome is most commonly observed in conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, and ulcerative colitis, where inflammation and mucosal injury result in altered barrier function. However, there is growing interest in the potential role of leaky gut in diseases outside the gastrointestinal tract, such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and neurological conditions. Despite these associations, the direct causality between leaky gut and these diseases remains unproven, and much of the evidence is still speculative.

Pathophysiology of Leaky Gut Syndrome

The intestinal barrier is a dynamic and multifaceted structure that includes several layers of protection. The first line of defense is the mucus layer, which serves as a physical barrier, preventing pathogens and harmful antigens from directly interacting with the epithelial cells. Beneath the mucus layer lies the epithelial layer, consisting of enterocytes connected by tight junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes. These intercellular junctions are crucial for maintaining the integrity of the gut barrier and regulating the paracellular transport of molecules.

Epithelial permeability is influenced by various factors, including stress, diet, and the microbiota. Under normal conditions, tight junctions regulate the passage of ions, water, and small solutes between enterocytes. However, under certain conditions, such as inflammation or stress, these junctions can become disrupted, leading to increased permeability. This can occur through mechanisms such as the dissociation of tight junction proteins (e.g., zonula occludens 1 [ZO-1], occludin, claudins), epithelial cell apoptosis, or alterations in transcellular transport.

Inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and proteases, can also contribute to intestinal barrier dysfunction. For example, in conditions like IBD, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) can induce tight junction protein degradation, leading to increased permeability. Additionally, environmental factors, such as the consumption of certain foods or exposure to toxins, may further compromise the barrier.

The Role of Stress and Dietary Factors in Leaky Gut

Increased intestinal permeability is often associated with a variety of stressors, including physical stress from intense exercise, psychological stress, and the use of medications like NSAIDs. These stressors can trigger the release of inflammatory cytokines and other mediators that disrupt the tight junctions between epithelial cells, resulting in leaky gut.

Dietary factors also play a crucial role in modulating intestinal permeability. For example, the consumption of foods rich in lectins, such as beans, grains, and nightshade vegetables, can contribute to gut permeability by binding to the gut lining and disrupting tight junction integrity. Gluten, found in wheat and other grains, has also been implicated in increasing intestinal permeability, particularly in individuals with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.

Conversely, certain dietary interventions may help restore the integrity of the gut barrier. Fermented foods, which contain beneficial probiotics, can support the gut microbiota and improve intestinal health. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish and supplements, have anti-inflammatory properties that help protect the intestinal lining. Other nutrients, such as zinc and vitamin D, are essential for the maintenance of a healthy gut barrier.

Clinical Measurement of Intestinal Permeability

Several methods exist to assess intestinal permeability, each with its strengths and limitations. The most widely used approach involves the oral administration of probe molecules, such as lactulose, mannitol, or sucralose, which are absorbed by the paracellular or transcellular pathways. The amount of these molecules excreted in the urine provides an indirect measure of intestinal permeability. Lactulose, a disaccharide, is typically used as a marker for leak pathway permeability, while mannitol, a monosaccharide, is thought to reflect permeability through the pore pathway. The ratio of lactulose to mannitol (L/M ratio) is often used as a diagnostic tool to evaluate barrier function.

In addition to urine-based tests, in vitro techniques using mucosal biopsies and Ussing chambers can be used to measure the permeability of intestinal tissues. These methods involve exposing tissue samples to probe molecules and measuring the transfer of substances across the epithelial layer. While these tests offer valuable insights into the mechanisms of leaky gut, they are not widely used in routine clinical practice due to their complexity and the need for specialized equipment.

Emerging technologies, such as confocal endomicroscopy and endoscopic mucosal impedance, may offer more non-invasive and real-time methods for assessing intestinal permeability. These techniques allow for the direct visualization of intestinal barrier dysfunction during endoscopy, providing a more dynamic assessment of gut health.

Treatment Strategies for Leaky Gut Syndrome

While the management of leaky gut depends on the underlying cause, there are several treatment approaches that may help restore gut barrier integrity and reduce inflammation.

Dietary Modifications

The first line of defense in managing leaky gut is often dietary modification. Removing foods that contribute to gut permeability, such as lectins, gluten, and dairy, may help reduce intestinal inflammation and restore barrier function. Dr. Steven Gundry’s research emphasizes the importance of eliminating lectin-rich foods and adopting a plant-based, lectin-free diet to improve gut health.

Fermented foods, such as sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, and yogurt, are rich in probiotics that help maintain a healthy microbiota and support intestinal integrity. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish like salmon, have been shown to reduce intestinal inflammation and protect the gut barrier. Zinc, vitamin D, and L-glutamine are other essential nutrients that promote the repair of the intestinal lining.

Supplements

Several supplements have been shown to support gut health and reduce intestinal permeability. L-glutamine, an amino acid, is particularly important for intestinal cell repair and has been shown to reduce permeability in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and Crohn’s disease. Probiotics, especially strains like Akkermansia muciniphila, may help restore a healthy balance of gut bacteria and improve barrier function. Zinc and vitamin D are also critical for maintaining the integrity of the epithelial layer.

Pharmacological Interventions

In some cases, pharmacological interventions may be necessary to manage leaky gut. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), while commonly used for pain relief, can exacerbate intestinal permeability. In such cases, clinicians may consider using alternatives that do not disrupt the gut barrier. Other pharmacological treatments, such as corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents, may be used in cases of autoimmune diseases associated with leaky gut.

Conclusion: Clinical Implications of Leaky Gut Syndrome

Leaky gut syndrome is a complex condition that requires a multifaceted approach for diagnosis and treatment. While current evidence suggests that dietary and lifestyle modifications can play a significant role in managing the condition, the clinical significance of increased intestinal permeability in non-gastrointestinal diseases remains unclear. Clinicians should be cautious in attributing disease causality to leaky gut without further investigation and consider it as a potential contributor to inflammation and disease progression.

Dr. Steven Gundry’s approach, focusing on dietary modifications to address lectin-induced inflammation, provides a useful framework for managing leaky gut in clinical practice. However, more research is needed to validate the role of leaky gut in various disease states and to identify effective, evidence-based interventions. As always, a personalized approach that considers the patient’s specific symptoms and underlying health conditions is essential for optimal management.